For many, a morning feels incomplete without the ritual of a hot cup of coffee heralding the day’s start. Beyond any doubt, coffee is the most popular consumed beverage in the world. You can enjoy this ubiquitous, enticing, and captivating elixir in any of its forms. But how did it become such a global phenomenon? Since we all love coffee, we’ll explore the history of coffee, from its origins to spread across continents and cultures and its different styles.

“Smell the roses. Smell the coffee. Whatever it is that makes you happy.”

Rita Moreno

- From Qahwah to Coffee: The Linguistic Journey

- The Origins of Coffee: Myth and Reality

- Coffee Conquers the World: From Middle Eastern Alleys to European Salons

- Seeds of Empire: Coffee Global Trade and Colonialism

- World’s Coffee Powerhouses

- The Many Faces of Coffee

- From Ancient Rituals to Modern Cafés

- The Art and Science of Coffee Preparation

- Masters of the Bean

- Crafting the Perfect Cup of Coffee: The Secrets of Connoisseurs

- The Bitter Truth: Unpacking the Ecological Cost of Coffee

- More Than Just a Drink

Today’s Focus of Attention is reader-supported. We sometimes include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission.

From Qahwah to Coffee: The Linguistic Journey

The voyage of the word ‘coffee’ reflects a rich history of cultural interactions, trade, and semantic evolution, spanning from Africa through the Middle East to Europe.

In English, the term ‘coffee’ comes from the Dutch ‘koffie’, which in turn was borrowed from the Ottoman Turkish ‘kahve’. ‘Kavhe’ was taken from the Arabic ‘qahwah’, a name that speaks about a type of wine with similar stimulating effects to coffee.

At the same time, the Arabic word ‘qahwah’ might have referred to the region of Kaffa in Ethiopia, where coffee plants were found.

Another theory suggests that it comes from ‘qaha’, an Arabic term meaning ‘to lack hunger’, in reference to the drink’s appetite-suppressing properties.

“I put instant coffee in a microwave oven and almost went back in time.”

Steven Wright

The Origins of Coffee: Myth and Reality

The legend has it that a goat herder named Kaldi discovered coffee in the 9th century in Ethiopia, Africa. He noticed his goats became more energetic and playful after eating the red berries of a plant, so he tried the berries himself and felt the same effects.

Kaldi then took some cherries to a nearby monastery, where a monk brewed them into a drink, which helped him stay awake during his prayers, and soon coffee gained popularity amongst the other monks.

However, this story, while charming, lacks historical evidence.

The earliest credible records date back to the 15th century in Yemen, where Sufi mystics used the beverage as a stimulant to aid their spiritual practices. And, like today, coffee beans were roasted, ground, and boiled in water to produce the bitter drink.

“To me, the smell of fresh-made coffee is one of the greatest inventions.”

Hugh Jackman

Coffee Conquers the World: From Middle Eastern Alleys to European Salons

Coffee migrated from Yemen to other parts of the Middle East, such as Egypt, Syria, and Türkiye, and as far as Persia, India, and Indonesia through trade and travel.

After spreading in those areas, private and religious coffee consumption turned into public coffeehouses, or qahveh khaneh, which became vibrant social hubs where people of all classes gathered to engage in lively discussions, play games, and listen to music.

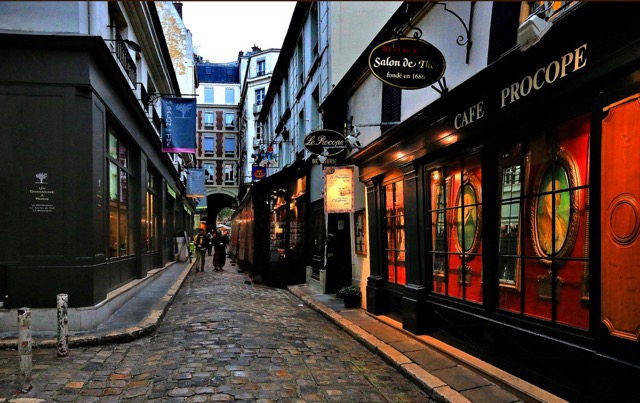

In the 16th century, merchants and travellers who had visited the Ottoman Empire introduced coffee to Europe, which years later led to the establishment of the first coffee house in Piazza San Marco, Venice, in 1645. Following, ‘cafes’ multiplied across Italy, France, Germany, and England.

In 1686, in Paris, “Café Procope” was founded, becoming the longest-running coffee bar in France, and in Italy, the oldest is Café Florian, which opened in Venice in 1720.

But the scope of this beverage did not limit itself to being a companion for talking and sitting. Scientists and artists drank it too, as a stimulant for creativity and innovation.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, ‘cafés’ played a pivotal role in fostering intellectual discourse, contributing to the era of the Enlightenment and the ideas that fuelled the French Revolution.

In London, Paris, and Vienna, these establishments, often regarded as ‘penny universities’, became hotbeds for critical thinking, the exchange of viewpoints, and information for philosophers, writers, and politicians. They all shared progressive thoughts and theories.

In America, the Boston Tea Party, a pivotal event in US history, turned coffee into a symbol of patriotism. This incident occurred on December 16, 1773, when American colonists, protesting against the British government’s Tea Act, which imposed taxes on tea, boarded ships in Boston Harbour and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water.

In the wake of the Boston Tea Party, drinking tea, which was imported from Britain, became seen as unpatriotic and loyalist. In contrast, coffee, which was not under British control, emerged as a patriotic alternative.

But the black beverage was not free from opposition and controversy.

Religious authorities denounced coffee as a “devil’s drink” and tried to ban it. Also, rulers feared that coffee houses were breeding grounds for rebellion and dissent – which indeed happened. Even medical experts warned that ‘the liquid delight’ could cause various health problems. Despite these fierce challenges, coffee continued to grow in popularity.

Seeds of Empire: Coffee Global Trade and Colonialism

As coffee consumption increased in Europe and America, so did the need for more production.

Back then, most of the world’s provisions came from Yemen and Ethiopia. But, in the 17th century, European powers began to set up plantations in their colonies in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America.

The Dutch were the first to cultivate coffee outside the Arabian Peninsula and Africa.

Pieter van den Broecke, a Dutch merchant, found a way to circumvent the Arab restrictions and acquired a few coffee beans from Mocha, Yemen, at the end of the 17th century. These beans were transported to Amsterdam, cultivated in the botanical gardens, and then taken to Java, Indonesia, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Suriname. This marked the beginning of coffee agriculture across Dutch colonies in Asia.

In France, King Louis XIV received a coffee plant as a gift, leading to the establishment of a royal greenhouse and the eventual spread of coffee culture in the kingdom.

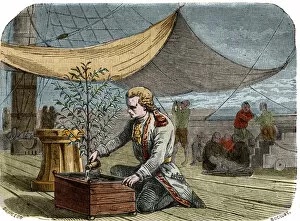

Gabriel de Clieu, a French naval officer, embarked on a daring and perilous voyage from France to Martinique with the mission to cultivate coffee in the New World. He carried with him a single coffee plant, a precious cargo from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Paris. But his journey was fraught with challenges, including harsh weather conditions, a pirate attack, and a near-fatal shortage of fresh water.

In an act of remarkable dedication, he shared his limited water supply with the little bush, ensuring its survival. His perseverance paid off when he reached the island, placed the plant, and it thrived in the Caribbean soil, leading to the expansion of cultivation in Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), and other Caribbean islands.

For their part, Spain and Portugal established farms in Central and South America.

In 1727, Francisco de Melo Palheta, a Portuguese Segeant-Major, was sent to French Guiana under the pretence of settling a border dispute. But his true mission was to get coffee seedlings, which the French were jealously guarding.

Unable to obtain these through official channels, he turned to charm and diplomacy. Palheta captivated the wife of the Guianese governor with his charisma, and upon his departure, she gifted him a bouquet with hidden, precious coffee young plants and fertile seeds.

These smuggled seedlings were the genesis of what would become Brazil’s massive coffee industry, turning the country, a Portuguese colony, into the world’s largest coffee producer and reshaping its economic and social landscape forever.

A few years after that, production expanded to other regions, such as Central Africa, and Southeast Asia.

An Overlooked Chapter in the History of Coffee

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the burgeoning coffee industry in Brazil and the Caribbean was reliant on slave labour. In Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, the rapid expansion of plantations coincided with a dramatic increase in the import of enslaved Africans.

The work-intensive nature of coffee cultivation, from planting and harvesting to processing the beans, required a large workforce, and slaves provided a cheap and coerced solution, fuelling the growth of the industry. Same applied to the Caribbean islands of Saint-Domingue, Jamaica, and Cuba, where the trade thrived on human exploitation.

The productivity and profitability of these plantations and the economy of colonial powers were built on the back of inhuman treatment.

World’s Coffee Powerhouses

Coffee is grown in over 70 countries across the globe, but some produce more than others. The following chart shows the top five:

| Rank | Country | Metric tons | Pounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brazil | 2,652,000 | 5,714,381,000 |

| 2 | Vietnam | 1,650,000 | 3,637,627,000 |

| 3 | Colombia | 810,000 | 1,785,744,000 |

| 4 | Indonesia | 660,000 | 1,455,050,000 |

| 5 | Honduras | 580,000 | 1,278,681,000 |

“I like coffee because it gives me the illusion that I might be awake.”

Lewis Black

The Many Faces of Coffee

The realm of black gold is summarised into four main branches:

Arabica

This is the most consumed type, accounting for around 60% of global production.

Arabica beans have a sweet and complex flavour with a lower caffeine content than other types. It is cultivated in high lands and tropical climates, above all in Central and South America, Africa, and Asia.

Robusta

As the second biggest, Robusta is close to 40% of the world’s supply.

Grown in low altitudes and hot areas, such as Brazil, Robusta beans offer a strong and bitter taste with a higher caffeine content than Arabica.

Liberica

With a unique and aromatic flavour, this rare coffee accounts for less than 2% of the global market. It grows at low heights and in humid weather, such as those found in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Excelsa

Excelsa is a sub-variety of Liberica, with a similar production and origin. Its beans have a fruity and tart savour with a medium caffeine content. Southeast Asia is home to this class, which is often blended with other types of coffee to enhance its sapidity.

These are the main categories on the market. But we have a special recommendation, which, despite being expensive, is worth mentioning.

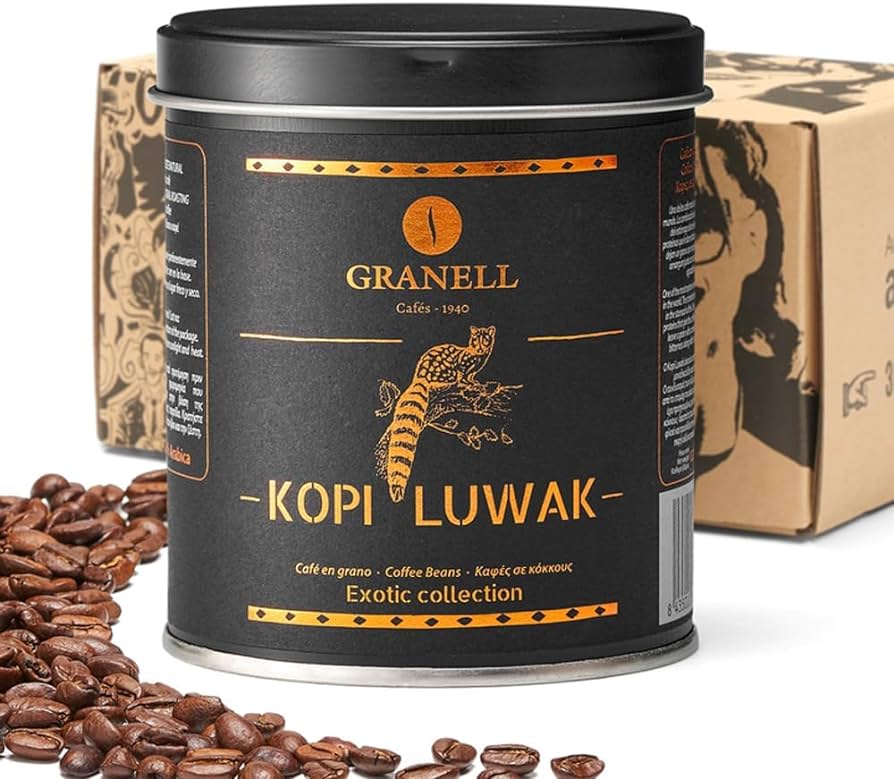

Civet Coffee

Known as ‘kopi luwak’, civet coffee is a singular type that is made from beans that have been eaten and defecated by the Asian palm civet, a small mammal native to Southeast Asia.

This little animal selects and consumes only the ripest and best cherries and then passes them through its digestive system, where they undergo a natural fermentation process that alters their chemical composition and flavour.

The beans are then collected, cleaned, roasted, and brewed to produce a smooth, rich, and aromatic cup of coffee.

Civet coffee is said to have less bitterness, with notes of chocolate, caramel, and earthiness.

Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Thailand are the major producers, but Indonesia leads the pack.

If you want to enjoy this class, you’ve got to pay between $100 and $1,300 per kilogramme, depending on the origin and quality of the product.

From Ancient Rituals to Modern Cafés

The culture of drinking coffee has evolved across distinct regions. Different methods of brewing, roasting, grinding, and serving have emerged to suit various palates and preferences. Here are a few ways:

Turkish or Greek

If you prefer this way, boil finely ground coffee with water and sugar in a small pot called a ‘cezve’ or ‘briki’. The birthplace of this technique is the 16th-century Türkiye, which became a favourite in the Middle East, Balkans, and Eastern Europe.

Cold Brew

This preparation results in a smoother and less acidic coffee than with hot brewing methods. Originated in Japan in the 17th century, it consists of coarsely ground beans in cold or room-temperature water for 12 to 24 hours.

Filter or Drip

This method involves pouring hot water over ground coffee held in a paper or metal sifter. The origin of this style finds its roots in Germany in the early 20th century and is most popular in America and Northern Europe.

Espresso

A concentrated form that is made by forcing hot water through coffee powder under high pressure. Its origins date back to Italy in the late 19th century, and is the base for other drinks such as cappuccino, latte, macchiato, mocha, etc.

The invention of the espresso machine is credited to Luigi Bezzera, a Milanese inventor, who filed the patent in 1901. Bezerra’s motivation was to reduce the time his employees spent on breaks.

Then, in 1905, Desiderio Pavoni purchased the licence from Bezerra and began manufacturing the machines under the brand ‘La Pavoni’.

“Life is too short for bad coffee.”

Gord Downie

The Art and Science of Coffee Preparation

| Type of Coffee | Description |

|---|---|

| Americano | A style of coffee prepared by adding hot water to espresso, giving it a similar strength but different flavor from drip coffee. |

| Black Coffee | Simply coffee without any added ingredients; straightforward and strong. |

| Cappuccino | A coffee drink consisting of espresso and steamed milk foam. |

| Espresso | A concentrated form of coffee served in small, strong shots and is the base for many coffee drinks. |

| Latte | Made with espresso and steamed milk, lattes have more milk than cappuccinos. |

| Macchiato | An espresso with a small amount of milk, usually foamed. |

| Mocha | A chocolate-flavored variant of a latte. |

| Cold Coffee Variety | Includes various iced or cold versions of coffee drinks. |

| Affogato | A dessert coffee that combines espresso and ice cream. |

| Cold Brew | Made by steeping coffee grounds in cold water for an extended period. |

| Frappuccino | A blended iced coffee drink with other ingredients such as sugar, milk, and flavorings. |

| Iced Coffee | Classic coffee served over ice. |

| Mazagran | A Portuguese coffee drink combining espresso, lemon, and mint. |

“Never trust anyone who doesn’t drink coffee.”

AJ Lee

Masters of the Bean

In this chart, you’ll find the top five ready-to-drink coffee kings:

| Rank | Company | Revenue (in billion USD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Starbucks | 23.52 |

| 2 | Nestlé | 21.09 |

| 3 | JAB Holding Company | 15.64 |

| 4 | The Coca-Cola Company | 10.44 |

| 5 | Dunkin’ Brands | 1.37 |

“Starbucks represents something beyond a cup of coffee.”

Howard Schultz

Crafting the Perfect Cup of Coffee: The Secrets of Connoisseurs

Tips on how to prepare the best coffee ever:

Buy fresh, roasted coffee beans from a reputable source

Look for a ‘roasted on’ date on the label and choose the freshest possible. Try different roasts, origins, and types to find your preferred flavour.

Store your beans in an airtight container at room temperature

Keep them away from light, heat, and moisture, and also avoid refrigeration, as this can affect their attributes.

Grind your beans right before brewing

The size depends on the method, but a medium-fine powder is suitable for most techniques. A burr grinder helps for a consistent and even grind.

Use filtered water heated to about 93 °C or just below the boiling point

The quality and temperature of the water may impact the extraction and taste of coffee.

“I have measured out my life with coffee spoons.”

T.S. Eliot

The Bitter Truth: Unpacking the Ecological Cost of Coffee

Producing coffee is one of the most profitable agricultural activities, but we cannot deny that it has negative impacts on the environment.

Deforestation

Coffee plantations often replace natural forests, which reduces biodiversity and habitat for wildlife. To illustrate, every cup of coffee consumed destroys around one square inch of rainforest.

Between the beginning of the 21st century and 2015, Robusta and Arabica crops replaced about 2 million hectares of forest worldwide. Deforestation contributes to climate change as trees absorb carbon dioxide and regulate the Earth’s temperature.

Also, the clearing of land for agriculture releases significant amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, exacerbating global warming.

Water consumption

Coffee cultivation requires tonnes of water, both for irrigation and production. For example, the coffee required for a single cup takes 140 litres of water to produce.

Climate Change

The more coffee, the more heat-trapping gases, which in turn affect production as they alter the conditions and quality of the crops.

Pollution

Coffee farming and processing use chemicals and pesticides that contaminate soil and water sources. In Brazil, the world’s largest producer, the application of agrochemicals increased by 190% in a decade.

A study published by Nature Climate Change shows that coffee production emits about 21.6 million metric tonnes of CO2 every year, similar to the emissions from over 4.6 million vehicles.

Another piece of research from University College London found that growing one kilogramme of Arabica coffee in Brazil or Vietnam and exporting it to the UK produces atmospheric pollutants equivalent to 15.33 kg of carbon dioxide on average.

More Than Just a Drink

Coffee is a fascinating and diverse beverage with a long and rich history. From its origins in Ethiopia and Yemen to its spread across the world, coffee has influenced and been influenced by various cultures and civilisations. At the same time, this liquid joy has been a source of income, pleasure, and inspiration for countless people. Farmers, traders, roasters, baristas, and consumers are part of a complex and interconnected global network. Are you a coffee lover? Please share with us how you make your perfect cuppa.

“Coffee is a language itself.”

Jackie Chan